Data Collection

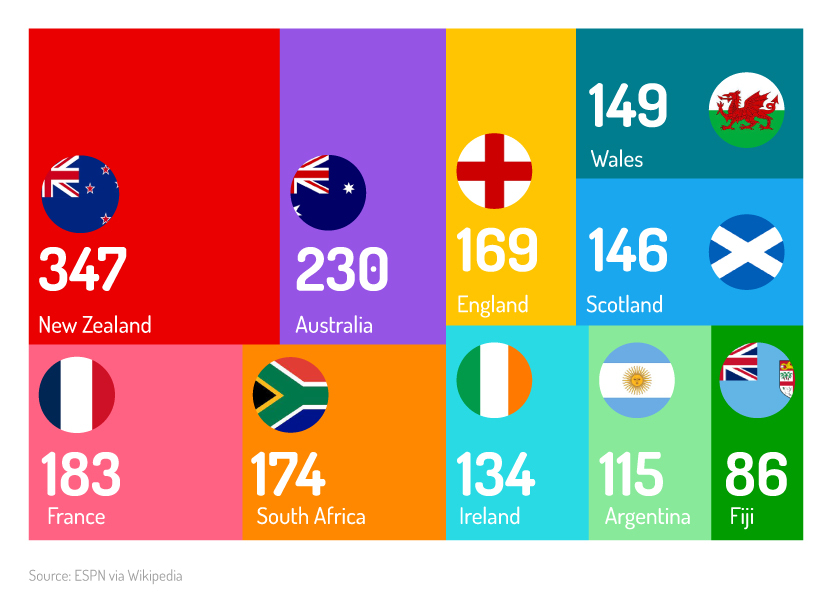

Data is all around us: think about weather forecasts, traffic data on Google Maps, statistics of your favourite sports teams, or even the number of likes on an Instagram post.

Every day, we use this data to make decisions.

We use weather data to decide what to wear; traffic data to decide which route to take to university; sports statistics to decide if our team has a chance to win their next match; social media data to decide if an influencer is popular or not; and much more.

Any statistical model or analysis is only as good as the input data.

No matter how sophisticated the analysis, if the input data is poor, the output results will not be any good.

This is known as the Garbage-In-Garbage-Out (GIGO) principle.

As good data analysts, it is our responsibility to ensure that, whenever we are involved in data collection, it is done correctly, in a systematic, accurate, and unbiased way.

The goal of statistical data collection is to gather information that can be used to find patterns and trends, accurately answer questions, test hypotheses, and make evidence-based decisions.

The process of data collection is multi-faceted.

It involves identifying what we want to study, choosing the right methods to collect the data (like surveys, experiments, observations, or finding secondary or tertiary data sources), and ensuring the information is reliable and representative.

By learning about data collection, you will gain tools to make informed decisions in a variety of fields, from science and business to social issues.

It will also equip you, as a data analyst, to help others to do so.

Q: Can you think of other sources of data that you use to make daily decisions?

How reliable do you think these sources are?

Planning data collection

Before you start collecting data, it is crucial that you plan how you are going to do it.

You will need to ask yourself (at least) the following questions:

- What is the question I am trying to answer?

- What/who is the population I am studying?

- What kind of information do I need from the population to answer this question?

- How can I obtain a dataset that will be representative of the information I need from this population?

- How can I obtain such a dataset in an ethical way?

Example 1: Raheem wants to open a new resaurant on Hatfield campus.

Before doing this, he wants to know what the students think of the restaurants and fast food places already available on campus, in terms of the cost, freshness variety and taste of food.

Following the data collection planning questions above, he gives the following answers:

- What is the question I am trying to answer? What are the perceptions of students on Hatfield campus about the cost, freshness, variety and taste of food already available on campus?

- What/who is the population I am studying? Students on Hatfield campus.

- What kind of information do I need from the population to answer this question? Answers from students about their perceptions of the available food options.

- How can I obtain a dataset that will be representative of the information I need from this population? I can conduct a survey of students on Hatfield campus.

- How can I obtain such a dataset in an ethical way? By obtaining the relevant permissions to conduct such a survey from the University, and to obtain clear consent from every student I ask, after I have explained the purpose of the survey. I will also keep the students’ answers anonymous.

Example 2: Tebogo is an analyst for a private security firm operating on the Hatfield City Improvement District (CID).

Her security firm has recently employed a new strategy to combat theft.

She wants to know whether thefts have decreased since they employed the strategy.

She answers the questions as follows:

- What is the question I am trying to answer? Have thefts in the Hatfield CID decreased since our security firm employed its new theft-prevention strategy?

- What/who is the population I am studying? Everyone working in, living in, or travelling through the Hatfield CID.

- What kind of information do I need from the population to answer this question? Theft statistics from all relevant police stations whose precincts overlap with the CID.

- How can I obtain a dataset that will be representative of the information I need from this population? I can request crime statistics from the relevant police stations.

- How can I obtain such a dataset in an ethical way? By obtaining the relevant permissions from the SAPD, the relevant persons at the police stations themselves, and signing any necessary agreements about my use of the data.

Example 3: William is an ecologist who wants to determine if a new pesticide-free anti-fungal treatment he has developed will keep maize safe from fungal infections.

Below are his answers to the data collection planning questions:

- What is the question I am trying to answer? Whether my new anti-fungal treatment works to protect maize from fungal infections.

- What/who is the population I am studying? Maize plants.

- What kind of information do I need from the population to answer this question? Data on the health of maize plants that were given the treatment, and maize plants that were not given the treatment, when exposed to fungi.

- How can I obtain a dataset that will be representative of the information I need from this population? By planting two fields of maize, giving one the anti-fungal treatment and leaving the other without treatment, and then exposing them both to the fungus.

- How can I obtain such a dataset in an ethical way? By making sure the fungus cannot spread to any other plants or crops.

Class Exercise Question 1: You are asked to determine the favourite movie of first-year mathematical sciences students in your class.

Answer the data collection planning questions at the beginning of this section to determine what your intended dataset is, and how you will collect it.

Then, collect the data by asking some of the other students in the class what their favourite movie is.

Reminder of the data collection planning questions: 1.

What is the question I am trying to answer?

2.

What/who is the population I am studying?

3.

What kind of information do I need from the population to answer this question?

4.

How can I obtain a dataset that will be representative of the information I need from this population?

5.

How can I obtain such a dataset in an ethical way?

Primary data collection

Primary data is collected first-hand by the researcher in order to answer a specific question or questions.

Examples of primary data collection include conducting interviews and surveys to ask about people’s opinions and experiences; conducting experiments in a laboratory; collecting field data, such as animal tracking data; and taking direct measurements (e.g. the chemistry of plants, or the weight of animals).

Primary data is complex and resource-intensive to collect.

It also requires an in-depth understanding of the answers to the data collection planning questions in the previous section.

When you collect primary data, it is your responsibility to ensure that the correct data is collected in the correct way, and that the data is representative, unbiased, and ethical.

We will learn more about representative and unbiased data in the section on evaluating data.

Exercise: For each of Examples 1-3 in the previous section, identify the type of primary data collected (survey, experiment, field data, or direct measurements), or indicate if it was not primary data.

Class Exercise Question 2: Is the dataset from Class Exercise Question 1 a primary, secondary or tertiary dataset?

Can you obtain the data through surveys, interviews, experiments, field data, or direct measurements?

Secondary data collection

Secondary data is data that was collected by a different researcher for a purpose that is different from the current study.

Examples of secondary data include data from the national census, marketing data collected by a company, crime data, social media data, and more.

Secondary data collection is usually done in one of the following ways:

- By approaching the custodian of the primary data and obtaining their permission to use the data. This is usually done with sensitive data like public health or crime data.

- By downloading an open dataset from the internet.

- By webscraping or performing other techniques to gather data from the internet.

Q: Can you think of other examples of secondary data, and how you would collect them?

The main challenge when collecting secondary data is to make sure that it is the correct data to answer your research question.

Even though secondary data was collected by someone else, you as the analyst still need to ensure that the data is of good quality, and ethical.

Although the original data was not collected by you, you are still responsible for the ethics of the data as it pertains to your study.

If the data was collected unethically, you could still face consequences for using it.

This means that you cannot assume that the data is relevant and ethical.

Exercise: For each of Examples 1-3, if the data collected was not primary, identify the type of secondary data collected.

Evaluating Data

Once you have collected data (whether it is primary or secondary), you need to be able to determine if the data is good and fit for use.

This section explains the attributes of a good dataset, and how to check if it is relevant to the research question at hand.

The key aspects of a good dataset include relevance, quality, representativeness, unbiasedness, and impact.

Relevance

Relevant data is data that is applicable to the research question at hand.

The analyst must be able to use this data to answer their research question.

It must also be up-to-date for the purpose of the study.

It is important to ensure that data is relevant, since irrelevant or redundant data can clutter the analysis and reduce the efficiency of the study.

For example, if an insurer wants to answer a question about short-term insurance in 2024, a dataset on long-term insurance in 2024 would be irrelevant.

Similarly, a dataset on short-term insurance in 1996 would be irrelevant.

In order to ensure that primary data is relevant, one should collect only necessary data and regularly review datasets for alignment with the research objectives.

For secondary data, one should determine the scope of the data and date of collection.

Quality

The data must be of good quality.

This includes completeness and consistency.

A dataset is complete if it has minimal missing or incomplete data.

Gaps in data can distort the analysis, or require assumptions that may not be valid.

In order to ensure that primary data is complete, one should clearly indicate and document missing data, and where possible, implement strategies to fill gaps responsibly.

For secondary data, one should determine if any data is missing.

If there is a large amount of missing data, this may indicate that the dataset is not suitable.

If there are minimal missing values, one should use reliable techniques to impute missing data without making any undue assumptions.

As an example, missing data often arises in longitudinal health studies.

These studies typically attempt to determine the status of patients over time.

Missing values occur when patients do not show up for follow-up appointments and drop out of the study without explaining why.

This can happen if they simply forget their follow-up appointments; if they feel better, and no longer feel it is necessary to visit the hospital; or if they move away; or for a host of other reasons.

In such studies, it is therefore crucial to educate the participating patients on the need to attend their follow-up visits if they are able to.

A dataset is consistent if the data was recorded in a uniform and standardised manner across the dataset.

Inconsistent data formats (e.g., different date formats or units) can complicate the analysis and increase the risk of errors.

For consistency of primary data, it is important to use standardised units of measurements (if applicable), standard questions with clear instructions on how to answer them (if applicable), standardised data formats, and data entry procedures.

For secondary data, it is important to investigate whether the data formats and units are consistent across the dataset.

If they are not consistent, this should be remedied before the data can be used.

Inconsistencies slip into datasets more easily than one might suppose.

For example, if seven people are asked to write the date that classes started in 2025, they could each write it in a different way:

- 10/02/25

- 10 Feb 25

- 10th of Feb 2025

- 10/02/2025

- 10 February 2025

- 02/10/2025 (This one is strange, but it follows the date format used in the USA, MM/DD/YYYY. Sometimes, people’s phones or laptops might be set to the USA format by default, which can lead to these errors.)

- 2025/02/10 (This format, YYYY/MM/DD, is commonly used in Europe.)

If these answers were entered into an Excel spreadsheet, for example, Excel might not recognise all of them as dates, or might think that the date at item 6.

is actually referring to the 2nd of October 2025.

To ensure consistent dates, for instance, one could provide an example of a date (e.g. 31/12/2024) or a standard date format (e.g. DD/MM/YYYY, a common South African date format).

Representativeness and unbiasedness

The data must accurately represent the population being studied.

In most cases, it is impossible to capture data about the entire population of interest.

In Example 1, for instance, Raheem cannot possibly send surveys to every single student on Hatfield campus.

However, it is very important that he get data that represents the students on Hatfield campus.

If he only targeted students who studied business sciences, they would likely frequent the food outlets on that part of the campus.

This would not represent students who studied the humanities (as they are closer and thus more likely to visit food outlets in the Piazza) or students who studied engineering or science (as they are closer to food outlets around the Aula lawn).

Discuss: Consider Examples 2 and 3.

In each of these examples, discuss whether it is possible to obtain data on the whole population under study, and what the factors are that limit how much of the population can be observed.

An unrepresentative dataset is in danger of being biased.

Bias occurs when the data over-represents some members of the population, and under-represents others, or if it represents some members of the population in an unduly positive or negative light.

In Raheem’s case, the worst that could happen is that he might make an unsound business decision.

But, in the real world, bias can have extremely serious consequences, such as denying an applicant a bank loan based on their gender or race.

Bias can enter a dataset during collection, processing, or even during the interpretation of results.

We will consider the following types of bias: selection, measurement, sampling, confirmation, and historical bias.

Selection bias occurs when the collected data is not representative of the population being studied.

In Raheem’s case, only handing out the surveys to students purchasing on-campus meals would exclude students who did not buy food on campus.

This could exclude students who do not buy on campus meals for financial, health, or other reasons, which could lead to a loss of valuable information for his business.

Measurement bias happens when data collection tools or processes systematically record data incorrectly.

In Example 3, William needs to measure the response of maize to the fungal infection using specific tools.

If one of the tools were defective, this would introduce a systematic error into his dataset.

Sampling bias arises when some members of a population are more likely to be included in the sample than others.

For example, a poll on eating habits that only targeted shoppers at a butchery would not be likely to represent any vegetarians.

This would undervalue vegetarians’ opinions and experiences.

Confirmation bias arises when data collectors (or analysts) unintentionally focus on results that align with what they expect to see.

In Example 3, William might unintentionally place more importance on results that show that his anti-fungal treatment works.

In Example 2, Tebogo might expect more crime to occur around hubs of transport, such as the Gautrain station and bus stations, and unintentionally ignore crimes happening at other locations.

In Example 1, Raheem might expect students to be dissatisfied with the cost of food on campus, and unintentionally pay less attention to the surveys of students who were satisfied.

Unlike some of the other biases, confirmation bias is something that all of us struggle with every day.

Think about it: when you are watching sport, are you likely to think that the referee is being unfair to the team you expect to win, and ignore the penalties issued to the team you expect will lose?

When you are planning an outdoor event, are you more likely to believe weather forecasts that predict the good weather you are hoping for?

When you are reading reviews of skincare products, are you more likely to believe positive reviews on the brands you trust, and disregard negative ones?

Are you more likely to trust the opinions of people who already have ideas that are similar to your own, as opposed to people who have different opinions?

If confirmation bias leads us to make decisions that affect our health, financial decisions, or ideas about the world, it can affect us negatively.

- Historical bias occurs when past data is used that is inherently biased due to historical circumstances. This can lead to decisions that are not appropriate to the current day. In Example 2, if Tebogo obtained crime data from before the Hatfield CID was formed, this data would not enable her to make decisions about crime in 2025. In Example 1, if Raheem had data from before the COVID-19 pandemic, he would be misinformed about the food vendors available on Hatfield campus (following the COVID-19 pandemic, some food vendors closed and other new vendors opened businesses on campus). In the worst case, like confirmation bias, historical bias could be used to discriminate against people from certain demographic or religious groups. For example, historical data about approving bank loans or hiring employees in a company could discriminate based on race and gender, while past data about the adoption of children into stable homes could reflect historical stances on sexual orientation or single motherhood. Historical bias could potentially perpetuate inequality.

Discuss: What other examples of these different types of bias can you think of?

How do you think they can enter a dataset?

How would you avoid bias in data collection, and in daily life, to ensure informed choices?

Impact

The last aspect of evaluating data is that the data should not have a potentially harmful impact.

Irrelevant or poor quality data could lead to incorrect, uninformed decisions, while unrepresentative and biased data could be directly harmful by perpetuating misinformation.

Thus, ensuring that data is relevant, good quality, representative and unbiased goes a long way towards decreasing any potential harmful impact.

However, even relevant, good quality, representative data could be potentially harmful, depending on its nature.

Sensitive data like public health data, crime data, or any data is not adequately anonymised could be potentially harmful if distributed incorrectly. A good dataset could be misused by an unqualified or malicious user. Thus, it is important to ensure that sensitive data is stored securely and only shared with those who have the relevant access rights.

Examples

Example 4 (continuation of Example 1): Raheem has finished collecting surveys from students about their perceptions of the food available on campus.

He inspects his dataset using the key aspects above, and comes to the following conclusions:

- Relevance: Since this was primary data, it was collected by the investigator to answer his specific research question. The data is up-to-date. It is thus relevant.

- Quality: The surveys that were given to students were standardised. All students received a copy of the same survey, with clear instructions on how to answer each question. Thus, the dataset is consistent. Furthermore, nearly all of the respondents answered all the questions. Thus, the dataset is complete.

- Representativeness and unbiasedness: Students from all across Hatfield campus were asked to fill in the survey. This included students from different years of study, different degrees and different faculties, as well as diverse demographic and socio-economic backgrounds. Thus, the data represents the diverse student body on Hatfield campus. Furthermore, surveys were handed out to students at a variety of spots on campus, including far away from any food vendors, and regardless of whether or not students were eating purchased food, home-made food, or not eating at all. Thus, there was little if any bias.

- Impact: The data should not have a potentially harmful impact. The data was anonymised, so that students’ answers on the survey could not be linked to their identities in any way. Any mention of specific restaurants or food outlets was also removed, so that no student’s opinion could be linked to any existing vendor on Hatfield campus. Thus, there is very little chance of any potentially harmful impact on either students or food vendors.

Example 5 (continuation of Example 2):

- Relevance: Since this was secondary data, it is important to consider its relevance. Since Tebogo obtained the data from all police precincts overlapping with the CID, and obtained it for the specific timeframes she wants to study, the data is relevant.

- Quality: There was some missing data, but the data is complete enough to be used. Data was entered mostly consistently. The data quality is adequate.

- Representativeness and unbiasedness: Crime data is, by nature, somewhat unrepresentative, since only reported crimes are part of the dataset. Thus, certain crimes are less likely to be represented adequately. This could include minor crimes, like the theft of inexpensive items, or serious crimes where the victim is afraid to come forward, such as domestic violence. Therefore, Tebogo must account for the possible unrepresentativeness in the data, and make use of additional techniques or data, such as underreporting estimates, in her analysis.

- Impact: Since the police removed all data that could identify individuals, the crime datasets cannot be used to harm any individual. Still, care must be taken that the data is not accessed by anyone except Tebogo and the other authorised people in her company.

Example 6 (continuation of Example 3):

- Relevance: This is primary data collected by the researcher for his specific purpose, thus it is relevant.

- Quality: William meticulously collected the data and ensured that it was complete and consistent.

- Representativeness and unbiasedness: The data was collected in a carefully climate-controlled and contaminant-free environment. This removed the effect of any potential confounding factors on the results.

- Impact: Data showing the effectiveness of a treatment can be sensitive before the treatment is subjected to further testing and approval by government authorities. Uninformed individuals might try to use a similar treatment on their crops, and if the treatment has not been conclusively tested and approved, this may lead to bad outcome such as crops dying, or becoming unfit for consumption.

Class Exercise Question 3: Evaluate the dataset you collected in Class Exercise 1.